Art as Experimental Politics: a Review of Vid Simoniti’s Artists Remake the World: A Contemporary Art Manifesto

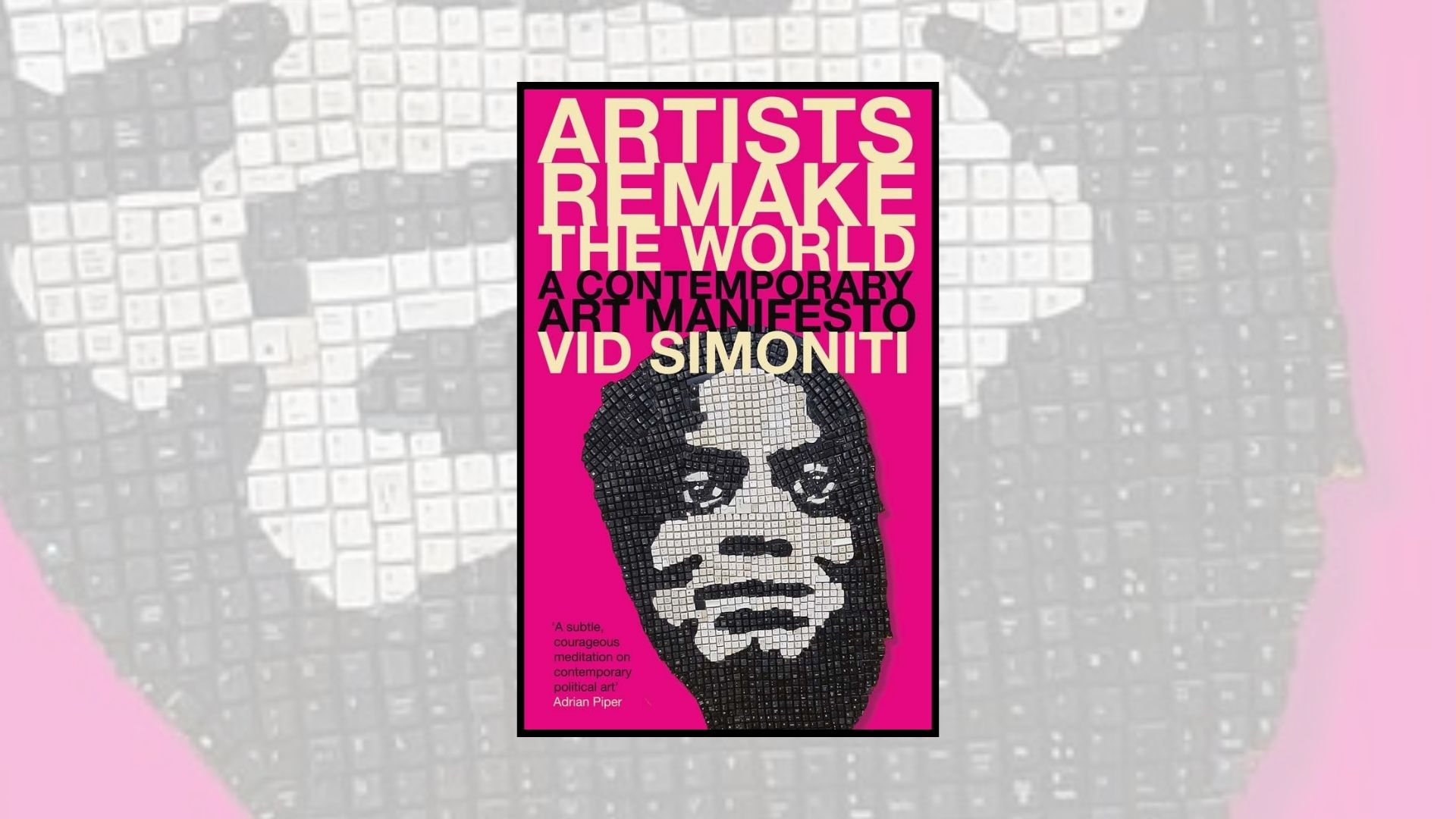

We live in an ever-increasing political world where art and politics cannot be as easily separated as before. Vid Simoniti’s recently published book, Artists Remake the World: A Contemporary Art Manifesto, uses examples of contemporary exhibition-based art projects to investigate the relationship between art and politics. Simoniti begins by asking the broad question “what can art do for politics?” (p. 9), and offers a possible answer by emphasizing art’s unique approaches towards political change. As Simoniti explains: “Art … can help us achieve a kind of looking, a kind of understanding. … Art is an experimental form of politics,” (p. 10).

One way art and politics interact in the gallery space is through activist art. Simoniti describes an important contribution of art for politics, since art aids political change through “conceptual clarification of the movement,” (p. 68). Art helps us by providing unique ways of seeing the political crises we face and possible solutions forward, which is different to listing facts or assessing political debates. In other words, we can become aware of a political aim through facts or debate, or we can be creatively shown a political aim through art. Art as creative action allows an audience to learn more about politics, but Simoniti’s distinctive point is that art allows politics unique conceptual clarification: “By reorganizing perception, art becomes relevant to politics,” (p. 84).

In a later chapter most interesting for Open Eye Gallery’s current LOOK Climate Lab 2024 exhibition, Simoniti describes contemporary ecological art, or ‘eco art’, as including “…three dominant artistic approaches: artists trying to instill a sense of emergency in their audiences, create a sense of solidarity with non-human nature, or impress the audience with human ingenuity in finding solutions,” (p. 132). We can understand these points further through comparing Simoniti’s claims with the artworks on display with the LOOK Climate Lab.

For the first approach found in eco art, Simoniti claims: “…emergency-inducing works … attempt to make tangible the climate disaster in the here and now,” (p. 133). We can see this through Cirrus Aviaticus by John Davies, whose photographs document jet engine exhaust fumes in the skies above Liverpool and Lancashire. However, Simoniti describes the difficulty in representing climate emergencies as an enduring crisis: “… it seems questionable to me as to whether art can truly sustain a sense of emergency, since the very emotional structure of emergency tends to be fleeting,” (p. 133). We can see images of exhaust fumes in the sky and sense a state of emergency, but could this image of emergency last long enough to enact positive change?

For the second approach, Simoniti describes the difficulty with eco art created by humans for the purpose of solidarity with non-human nature: ‘Human empathy is a fickle thing,” (p. 135). He explains further that even towards fellow humans, which we all typically agree deserve empathy, we often act without empathy for their problems. We can see this idea through the project Strange Eden by Mario Popham, whose photographs and site-specific materials explore whether society can offer empathy for postindustrial green spaces. If this project convinced audiences to adopt attitudes which give empathetic solidarity with non-human nature, would this solidarity lead to a better ecological future?

For the third approach, Simoniti describes intervention-based eco art as art “which often arises out of collaboration,” (p. 136). Artists often collaborate with non-art groups to enhance their overall message and impact, as seen with Home Grown Knowledge by Gwen Riley Jones. For this project, the artist has partnered with the Royal Horticultural Society to document the importance of community gardens through photography. It would be interesting to compare the effect of Jones’ project without the partnership with the Royal Horticultural Society, or perhaps if the project partnered with another royal society: in what ways do partnerships between artists and royal societies enhance the political impact of art?

Overall, art can help us work through political uncertainty not by rehashing the same facts but by presenting them in a new, creative way. To conclude his book’s exploration on the importance of art for politics, Simoniti writes: “…contemporary art enters at those junctures where our ordinary modes of thinking have been exhausted … it can shape thoughts in ways a journalist, scientist, activist or politician cannot as easily achieve,” (p. 172). The power of art for politics, for Simoniti, is not to present new debates, but to creatively present debates in a new way that may cause us to rethink ourselves and our attitude towards the world around us.

Join Open Eye Gallery for the book launch of Vid Simoniti’s Artists Remake the World on 31 January from 6 pm – 8 pm. The book will also be available for purchase in our bookshop.

Look Climate Lab 2024 will be on free view at Open Eye Gallery from 18 January – 31 March 2024.

Text: Lauren Stephens

Cover image: Maurice Mbikayi, Unitled.

Lauren Stephens is Philosopher in Residence at Open Eye Gallery and a PhD researcher in the philosophy of art at the University of Liverpool.