Science x Fiction: The Scientific Imagination and Science Fiction

From H. G. Wells and Jules Verne to Margaret Atwood and Ursula K. Le Guin – debates about what science fiction is and isn’t have raged since its inception. Here, Glyn Morgan takes a closer look at the genre’s relationship with science…

Science fiction’s relationship with science can be complicated, but your personal understanding of that relationship influences so much: not least how you may define the genre and when you would say it started. We all feel like we can identify science fiction, although far fewer of us would probably be willing to offer a hard definition. More likely, we’d take an approach similar to that of American author and critic Damon Knight who said of the genre, ‘it means what we point to when we say it.’

What people will point to, however, varies wildly, both among the general public and academics. Many blog posts have already been written about the twice Booker Prize-winning Margaret Atwood’s feelings on the term ‘science fiction’. In a series of articles and interviews following the publication of her post-apocalyptic tale of genetic engineering, Oryx and Crake, she resisted the label ‘science fiction’ preferring instead ‘speculative fiction’. To her mind, ‘science fiction’ are those books that descend from H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, which treats of an invasion by tentacled blood-sucking Martians shot to Earth in metal canisters – things that could not possibly happen – whereas, [for her], ‘speculative fiction’ means plots that descend from Jules Verne’s books about submarines and balloon travel and such – things that really could happen but just hadn’t completely happened when the authors wrote the books.’ Whether she realised it or not, Atwood was rearticulating a debate which could be traced at least as far back as those self-same forbear writers.

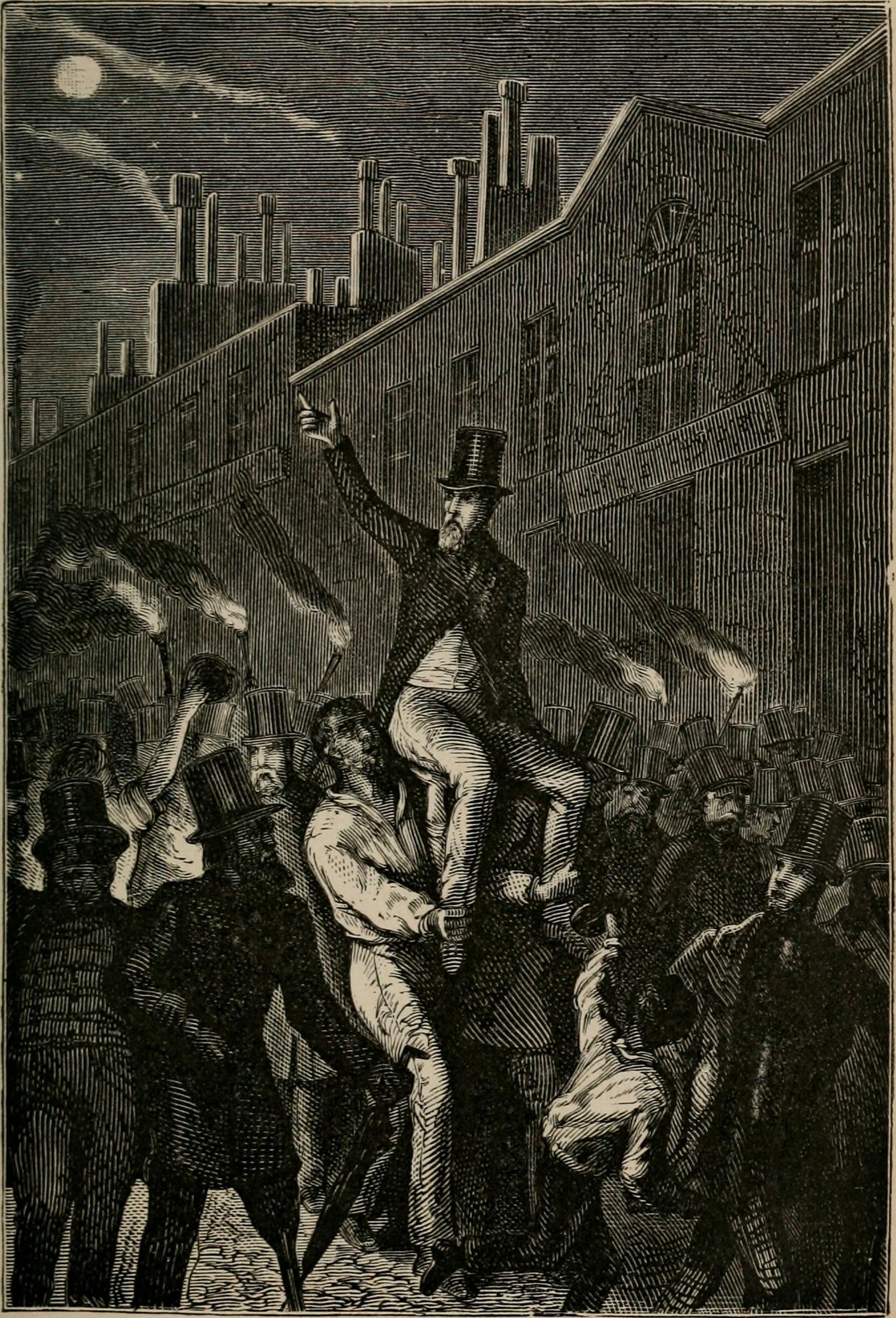

Both H. G. Wells and Jules Verne wrote stories in which their protagonists travelled to the moon. Verne published From the Earth to the Moon in 1865, whilst Wells’s The First Men in the Moon was serialised in 1900-1901 and collected into a single volume in 1901. In Verne’s story, the Baltimore Gun Club in the United States build a vast cannon, The Columbiad, load three men into a capsule which, in turn, is loaded into the gun and then fired at the moon. An article discussing the story in the London Pall Mall Gazette in 1880 describes the capsule and is actually the first use of the term “space ship”. Many of Verne’s stories are detail orientated and he drew strongly on what science and engineering knowledge he could acquire from the world around him. For example, the Nautilus, Captain Nemo’s famous submarine in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) was almost certainly inspired by the models and prototypes of submarines Verne witnessed at the Paris Exposition of 1867. For From the Earth to the Moon, Verne calculated the necessary trajectories and velocities required for such a trip and incorporated that work into his novel. By and large, the calculations are accurate; although the g-forces experienced by the capsule’s crew would have left them pulverised against the bottom of the capsule. He even selected a launch site, Stone Hill, Tampa, in Florida—only 140 miles West of the site that would be selected for moon launches by NASA a century later at Cape Canaveral—as he knew that the Earth’s rotation is faster near the equator, which makes achieving escape velocity easier.

Wells’s story, while later, does not feature any of this sort of logical extrapolation from mathematics, physics or engineering. In The First Men in the Moon, the trip is made possible from Lympne in Kent by using a new material able to negate the force of gravity. Invented by a local physicist named Cavor, he calls it ‘cavorite’. Cavor is convinced by a local businessman to construct a vehicle, a sphere of steel and glass, and to install cavorite panels which can be moved to steer the vessel and allow it to fly to the moon. Wells is not being lazy in his solution, and I’m not sure it’s possible to suggest one writer is more imaginative in their approach to the problem of reaching the moon than the other, but Wells was simply less interested in a story about how the moon could be reached and more interested in describing what might be seen when we got there. The focus of his book is less on the physics of cavorite, and more on the insectoid Selenites and their underground society on the moon. Verne’s novel concludes before his astronauts even reach their destination (this is covered in the 1869 sequel Around the Moon, although as the title suggests, even here a successful landing is not accomplished).

Nonetheless, when asked by an American reporter what he thought of the younger Wells’s writing, Verne replied:

‘His books were sent to me, and I have read them. It is very curious, and, I will add, very English. But I do not see the possibility of comparison between his work and mine. We do not proceed in the same manner. It occurs to me that his stories do not repose on very scientific bases. No, there is rapport between his work and mine. I make use of physics. He invents. I go to the moon in a cannon ball, discharged from a cannon. Here there is no invention. He goes to Mars [sic] in an airship, which he constructs of a metal which does away with the law of gravitation. Ça c’est très joli […] but show me this metal. Let him produce it.’

Ultimately, it’s questionable how much this matters. Verne may have been sniffy about Wells’s scientific method in his writing, or lack of therein, but as our understanding of the realities of spaceflight has evolved, we can now easily pinpoint the errors in Verne’s own understandings of the rules of the universe, however accurate they were by the standard of his day. Scientific accuracy is a moving target as our understanding of science improves and we develop technologies that change our society. This is as true for Verne and Wells as it was for Mary Shelley, writing almost a century before, citing early experiments with electricity by the likes of Galvani and Erasmus Darwin as part of the inspiration for Frankenstein (1818), considered by many the first science fiction novel. It remains true in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries; as the science fiction scholar Carl Freedman writes, over-zealous insistence on scientific accuracy to label something science fiction can lead to ‘patent absurdities’:

‘For example, one of [Isaac] Asimov’s science-fiction mystery stories (“The Dying Night”, originally published in 1956) depends for its plot resolution on the assumption that Mercury has a “captured” rotation; that is, that it turns on its axis at precisely the same rate that it revolves around the sun, and therefore that it contains areas where night is permanent. This assumption was faithful to common astronomical wisdom at the time of the story’s composition, but was disproved in 1965; the planet, evidently, does rotate much more rapidly than it revolves, and all parts of it are at one time or another exposed to sunlight. In an afterword to one reprinting of his story, Asimov humorously complained, “I wish astronomers would get these things right to begin with,” and he refused “to change the story to suit their whims”.’

Asimov was a professor of biochemistry as well as being one of the great science fiction writers of his time, and he did more to popularise scientific fields than most – not only through his science fiction stories and novels but also through his non-fiction work, such as Asimov’s Guide to Science. The idea that some sort of gatekeepers could eject writers like Shelley, Verne, Wells or Asimov from science fiction on the grounds of inaccuracy of science is almost as ridiculous as the idea of that same group having to constantly redraw the boundaries of the genre in line with every new development and innovation in STEM fields.

Far more important than the scientific accuracy of science fiction is the influence the genre has on scientific imaginations and a sense of scientific literacy. As a genre it makes its readers and viewers more comfortable with scientific terminology, ideas and concepts, and encourages them to consider the applications, implications and ramifications of those changes. I have spoken with computer engineers and artificial intelligence experts at places like IBM and Google who recall fondly reading Asimov’s robot stories as children, NASA has long touted the connections it has to Star Trek, and Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein adaptations inspired innovations in pacemakers. These are tangible, material benefits that have changed the courses of people’s lives, but even outside those, what is most thrilling to me about science fiction is how it opens up our minds to consider realities other than our own, it creates possibilities rather than shuts them down, and asks us to dream.

–

Dr. Glyn Morgan is an honorary researcher at the University of Liverpool where he completed his PhD thesis on speculative fiction and the Holocaust. He is now a curator at the Science Museum in London. He is the author Imagining the Unimaginable: Speculative Fiction and the Holocaust (Bloomsbury, 2020) and co-editor of Sideways in Time: Critical Essays on Alternate History Fiction (Liverpool University Press, 2019)This essay was commissioned as part of Imagining Disaster: Science Fiction X Contemporary Art. Join the conversation #ImaginingDisaster

Image: Verne, Jules. 1874. From the Earth to the Moon : direct in ninety-seven hours and twenty minutes, and a trip round it.,New York, Scribner, Armstrong (Creative Commons).