Artist Interview: Matthew Finn

Open Eye Gallery’s first Writer-in-Residence, Pauline Rowe, interviews exhibiting artist Matthew Finn about his photography practice. You can see Matthew’s work on display at Open Eye Gallery as part of the Jerwood/Photoworks Awards 2015 from 28 October – 18 December 2016.

Pauline Rowe: To get started – I’m really interested in how the camera and photography has framed and supported your relationship with your Mum. Can you remember the moment this made sense to you (i.e. was there a starting point you consciously remember) – was it when you first received the camera? And do you feel that the work is a joint (equal) collaboration with your Mum? And would she agree with you?

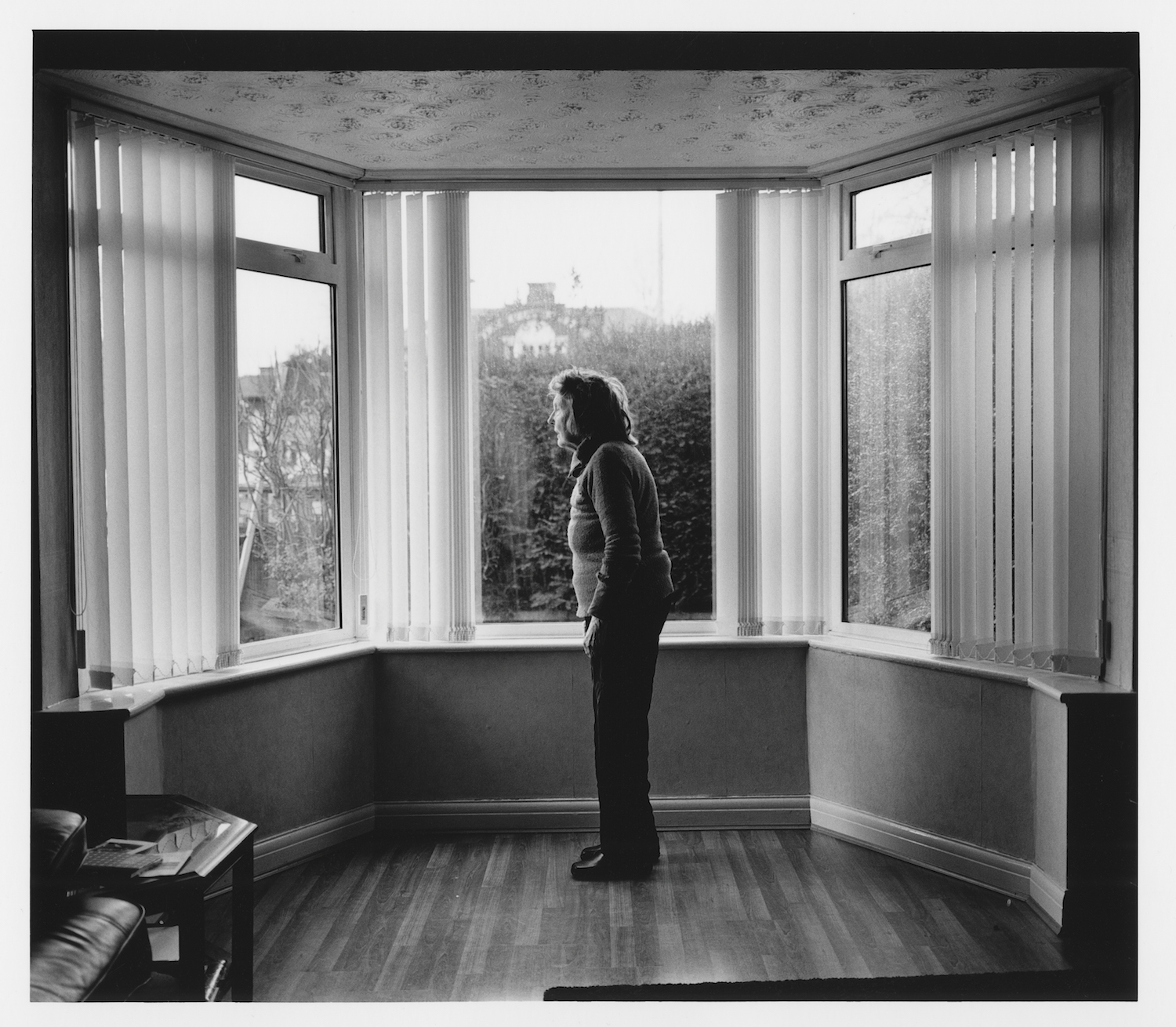

Matthew Finn: I’d been giving a camera several months before I started photographing my mother. I remember well the first photograph I took, at least the first one I printed in B/W. She was sitting on a dining room table chair positioned close to the patio windows so she could get the fresh air from the outside whilst looking onto the garden. It winter 1986. The light was bright but soft and cast lovely shadows onto the wall behind my mother.

As I said I’d had the camera for a while before this picture. What started the project was moving from our council flat to the semi-detached home that all the photographs are taken. We moved in the spring of ‘86. I think that first photograph and the new surrounds were the springboard to the series and its continuation.

The idea of the collaboration is an interesting one. At first I was just practising, using my mother as a figure within the frame. Once I moved away to University, several years after the start, that’s when it became a series worth investing in. Also the images seemed fresh each time I visited as they offered a sense of time compared to the daily images taken before I moved away.

I was starting to look at Nan Goldin and Sally Mann and was struck at how different approaches could be taken to long term projects. I liked the idea of something that was tangible and accepting at the same time.

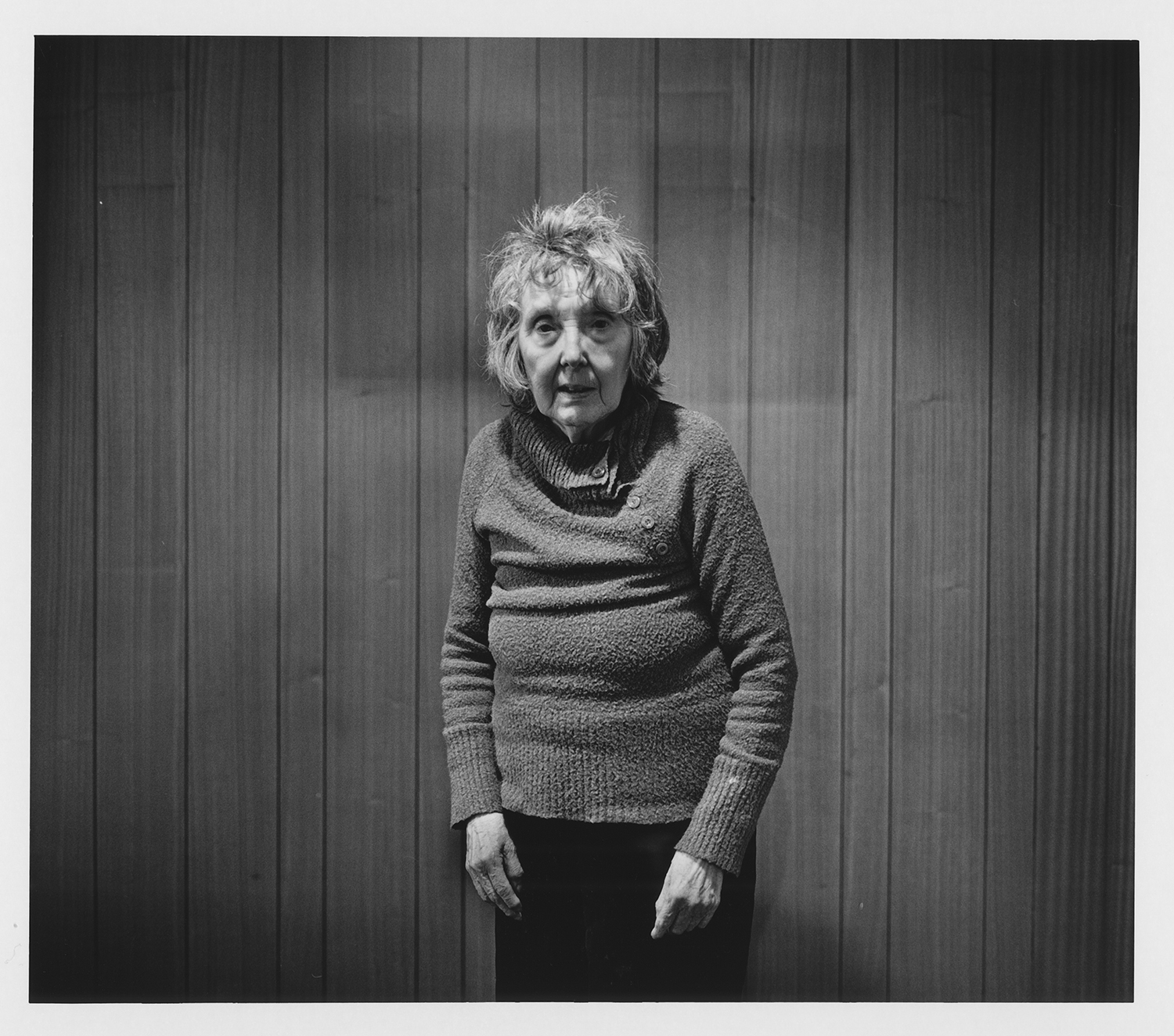

As time went on and I showed my mother the images she became aware of angles, her best side, quality of light, the closeness of the lens. I started to notice that she was coaxing me into the image she wanted. She knew how she wanted to be portrayed. This for me was a collaboration; it was unspoken we just continued with what I call a dance.

Photography became everything to us. I would not go back home without a camera and film and would be disappointed if the light was poor. I would have my camera ready first thing in the morning and photograph around my mother’s daily routine. We did this for 29 years in that house.

We never spoke about the project much. It was our routine. I had a camera and we made these images together. We needed each other. Would my mother agree on ideas of collaboration? I don’t know and now I never will.

PR: What is it that photographers can see that those of us who aren’t photographers miss?

MF: I don’t know if photographers do see things differently. What you’re left with is a trace. Putting work in a gallery is to do with confidence and acceptance. There’s a hierarchy about having work in a gallery that social media can’t have. Photographers see very small things in detail of what they want to photograph. It’s the opposite, in fact of what you suggest. I want to see the same as everyone else so that the audience can recognise it. It depends on the type of work you make. I like to make work about everything around me – family, students – photos where people can find something of themselves.

PR: You mention (in the Jerwood/Phortoworks interview) that in the Winter of 86 the light was casting lovely shadows onto the wall behind your Mum. Is photography about your relationship with light – or how you see the light?

MF: I love light and how light cast shadows. I’d never seen Van Gogh paintings before I saw them in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. There is a vividness of colour that I couldn’t replicate in life. It’s the same in Peter Greenaway films – with their sumptuous sets. Black and white made sense to me. Home for Mum was very brown – it didn’t lend itself to colour, but it did to light. Mum used to smoke – smoke is wonderful in light – and she used to drink – a crystal tumbler in the light is wonderful too. I don’t think I’ve changed from that constant in my work. To be good a photograph needs good light and a good subject. It’s only in war or when a singular event happens that you can’t aestheticise – then you can get away with no subject and poor light.

PR: You say your ‘Mother’ project started when you moved from your Council flat to the house where all the photos are taken. What was it about this move that was important to you and your Mum?

MF: It was a Council estate where you rented from the Council – it was rough and getting rougher. We lived in a top floor maisonette. To move to a house with a garden was amazing really. I was 16 and there was space to manoeuvre. I’d just left school. I hadn’t done particularly well, although I did enjoy school. The move came at a time when I was trying to figure out who I was. Photography worked on a lot of levels. It was instantaneous. The immediacy and the freedom. Slight independence. The camera exaggerated that independence and I enjoyed it. I couldn’t imagine not finding the camera. There are lots of things that made the work the way it is. The TV series Butterflies by Carla Lane – there was a lot in that series of a singular woman dreaming of a different life. I wanted to isolate Mother from the rest of the family. So we could have time together. The longevity of the project cuts through the question of how to avoid sentimentality. Here you see a person ageing.

PR: You talk about practising, using your mother in the frame. You were looking inside your house rather than outside – do you think this is unusual?

MF: Duration makes it unique. As a working-class boy there’s no way I could make certain types of work. Here you have a subject, you can keep on doing it and there are many of the same (Images). This is how we’d communicate. It’s ritualistic. This is what would be happening. It’s my point of view – as I lived in the house. We all had our own space. Lots of photos were taken from my mother’s routines and it’s how I had a conversation with her. It became important – part and parcel of our routine – taken for granted. My mother was a willing participant in this ‘dance’. In many ways she was directing me. I valued the time – it was over 30 years of her life – an incredible gift. I never questioned it or worried. Mum lived with her brother for 76 years and they had very defined roles in the home. He earned good money. There was a traditional division of labour. He provided Mum with security. Uncle paid for the house (£33,000 in 1986). He changed the destination. Mum couldn’t afford boxes of photographic paper. He was my father really. There was a confidence mother had. I wanted to portray mother as a heroine.

Once I moved away to University it became a project worth investing in…

PR: Is there a sense in which the photos are your life, not just evidence of it but how you see and understand – maybe remember your life? Do we find self-portraiture here?

MF: Photography is everything. I don’t think it’s particularly healthy. I look after my mother. There’s no escape. It’s so full on now in the last few years. If I start showing the work I don’t know if people like it. It’s public. I feel compelled to push it further. I want her to be recognised. Absolutely.

It is common. Dementia. There was not time to think about it. I was in Texas in 2014 and Uncle needed a pacemaker. But they didn’t operate in time and he was dead. 21st May. This was a catalyst when her brother died. She has mixed dementia and he had been protecting her. She won’t stop moving. There are two images I’ve taken in the Home. We can’t collaborate now. Before, it was a photographic device to entrap my mother, and she could leave the house. Now she’s mentally trapped in her own mind and physically trapped in the Home. I’ve taken photos on my phone, soft images for me, but they don’t mean anything.

PR: How did the greater gaps of time help with the series?

MF: I don’t think it will be chronological. We are moving through time but not chronologically. It’s more a walk through the house to give a sense of change, time, taste, environment. A sense of semi-detached Englishness. Not in terms of the North – that’s just a back-drop. I never wanted it to be a kitchen sink drama. There are some clues, but very few. Maybe more of Uncle wearing a flat cap. But if I had put mother in the city – images in Leeds – that would have been very different. Everyone knows the punchline. The edit constantly changes. I don’t want it too obvious.

PR: Can you say more about how looking at Nan Goldin or Sally Mann’s work helped you to consider or think differently about your own work?

MF: I like the duration. Emmet Gowan’s work is an incredible series. Beautiful lyrical work of his wife Adrienne, showing the fragile nature of the skin. Photography shows you physical change. I liked the Seven Up TV series – there was a sense of a different life. An honesty and openness. The thing with this type of work is the inevitability about what will happen. Honesty.

I didn’t expect to be here 30 years later. The work will help. I photographed Uncle. How they occupied the space together. Mother will be a book. I’m working on that. Flexibility can change images on a wall but not in a book. Through the Jerwood-Photoworks award I’m working with a very good anthropologist, Elizabeth Edwards, who works like a detective and sees the work differently. She’s agreed to write the foreword for the book. I’m happy to collaborate.

PR: The way you describe your Mum as responding to angles and light – that she ‘knew how she wanted to be portrayed’ – gives a strength to her place in the work as collaborator rather than simple subject. Almost that she became more of an artist?

MF: Mum had no artistic ambition. That would have been so out of kilter, growing up in the second world war. It wasn’t a working-class option…It still isn’t. There’s a need for backing, which is why the Jerwood award helps. I have a burning desire to show my mother to the world. I suppose I need my uncle. He was my patron.

PR: I want to pick up on what you said earlier – about your photography of your Mum being like a ‘dance’?

MF: Yes there was a sense of movement – ‘too close”, “to the left,” ‘to the right,” – but it was not a power struggle. But an act of theatricality. It became so embedded in routine eg. cooking Sunday lunch, there was tremendous security. A lot of time the photos were punctuations. We needed to spend time in the living room. There was a rhythm, an instinct – something not happened for a while. Always thinking of an audience. It was 25 years before I showed anyone the work – Bridget Copeland from The Guardian and Dewi Lewis.

PR: You also said earlier “photography became everything to us” ?

MF: Everything I do is collaborative. I’ve been working with students for over 20 years. In some ways I prefer to work closer to an auteur (film theory)- but there are no commercial constraints, because I want to do a certain kind of work- to uncover peoples’ lives. You can do this in 20 pictures over 20 years. I only take photographs in places and backgrounds real to the person – with students it’s the college or their home. Now the reason for doing it is more for my mother – with the award and because of Jean’s (Mum’s) illness.

PR: Given how you work, what do you think of work in a studio?

MF: It is false. False emotion. You have to construct an emotion. The context is part of the whole. I wouldn’t want that backdrop to be denied or to be taken away. One exception I can think of is Richard Atherton’s photos of his Father which he took in his studio. Also I haven’t been based in Leeds since 1989. I was only 3 years in the house, the rest of the work came from me visiting.

PR: What about technical stuff?

MF: All the work with Mum is on Leica Rangefinders. I do everything myself but I need a dark room now. Photography costs. Technology changes. You can’t teach technique any more given digital technology. For me what’s important is image, sequence and narrative.

PR: What does it mean to be a winner in the Jerwood-Photoworks Award? What did it help you to do that would have been difficult otherwise?

MF: My wife entered my photographs into the competition, not me. Martina sees the potential of the work and she wanted it to be recognised. It’s a finished body of work. I showed it sensitively. It’s inconceivable that young people now would make work like this. I had a range of ten projects on the go – all long term. I’ve been taking photographs of Prague since 1987. And my wife’s family. It only occurred to me recently that I took the first photo when my mother was 50. It’s only 5 years off for me – to reach the same age. How might I continue? – I might give my son a camera and see what he makes of it.

PR: In her essay “The Greys” Elinor Carucci says your works seems “curiously closer to the work of women artists than men..’ – what do you make of this?

MF: All my adult life it has impacted. I was always a quiet back-seat passenger. Mother would talk and talk and talk. Maybe photography was my way of getting into the conversation. Whether they are self-portraits or not – I suppose there is a reverse mirror image of me in the same moment in time. Physically there in each scene though I am not visible.

PR: Your work conveys change, time, fragility – is there anything you’d like to add?

MF: It all starts with the quality of light and then the every day things Mum would do. What mothers do for children. We see this in poor countries, mothers walking miles for water and hardship. When Mum worked she would get 2 buses and walk miles to drop me off at her sister’s before she took the same journey to work. She worked in a Jewish Textiles firm and later in a Bakery where she made cakes and sandwiches. It was important to document this labour – what mothers do. Regardless. A motherhood that’s not touchy, feely.

PR: Are there Catholic sensibilities at play in your work?

MF: I suppose there’s something of the quality of light, backlight. I love Easter and Christmas and there are certain values that are important. Trying to be a good person.

PR: Do you know how people receive the work? Does it matter?

MF: I like to talk to people where the exhibition is shown. The response in Bradford and Belfast was good. I suppose Liverpool sits the closest (in terms of the city). There’ll be 19 photographs in the exhibition and somewhere between 60-80 in the book from an edit of 400. It moves all the time. I have thousands of prints and 40 boxes of negatives. It needs an archivist.

—

About Pauline Rowe, Writer-in-Residence

Pauline first got the chance to work with the Gallery through the LiNK programme at the University of Liverpool and continuing work is being supported by the universities’ Centre for New and International Writing. She has 2 poetry collections, also works as a poet delivering projects at Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, and is currently doing a PHD at Liverpool University. Pauline lives with her husband and 6 children.